Improving the accuracy of website carbon emissions estimates

Existing models for website carbon emissions are good for reaching a ballpark figure of website CO2 emissions. I touched on that last year in Website carbon: Beyond data transfer. Models like the Sustainable Web Design model are extremely useful for providing an estimation framework, especially for developers who don’t have domain knowledge in the digital emissions space.

The importance of this cannot be understated. As more companies start thinking about digital emissions, dev teams are being asked to come up with estimates of their work’s impact. These teams are experts in HTML, CSS, JavaScript or some other combination of programming languages. Having models like Sustainable Web Design (SWD), which are fairly easy to understand & implement, provide a great starting off point for people looking at website carbon emissions for the first time.

Beyond the ballpark

Recently, I’ve had a few conversations with folks who’ve been working on different website carbon estimation pieces. In most cases, they have been regular developers who are looking at website emissions for the first time. In all cases, they have been using the Sustainable Web Design model and asked “how accurate is this estimate?”.

At the same time, I’ve been working on the next release of CO2.js. In it, we’re looking to address a common question we get from developers who use the library - how can I change X value in the SWD model?

Assumptions and generalisations

The SWD model contains a number of assumptions for how website data is loaded. Namely, these are:

- What percentage of visits to a site are new visitors (empty cache)

- What percentage of visits to a site are returning visitors (warm cache)

- What percentage of data for return visitors is downloaded (not served from cache)

The model also uses global average grid intensity (442 g/kWh) to generate carbon emissions estimates.

In reality, these values would differ from website to website, web page to web page, and user to user. It’s also worth noting that the underlying data that’s the foundation for the model is a few years old now, and should be revisited.

Producing more accurate estimates

Okay, so here’s the part that you’re probably clicked into this post for. How is it possible to improve the accuracy/meaningfulness of the carbon emissions estimates from a generalised model like Sustainable Web Design.

Before going further, though, I want to first acknowledge that the SWD model isn’t the only one around. What I go into below could also be applied to the 1byte model. There are also other methodologies specific to certain digital sectors - like DIMPACT, which I really want to get my teeth into during this year. Here’s a good paper on how Cambridge University Press have used it.

Adjusting the assumptions

To start with, let’s stick to what we’ve just been talking about. Most website owners should have access to data about new and returning visitors at least. Getting information about how much data is downloaded by returning visitors takes a bit of extra work, but can be estimated too.

The SWD model uses the following percentages for each:

- 75% first time visitors

- 25% return visitors

- 2% of data downloaded by return visitors

But for a real website, a blog post that’s gone viral on Hacker News might have 90% first time visitors, while a homepage might have more like 60% first time visits.

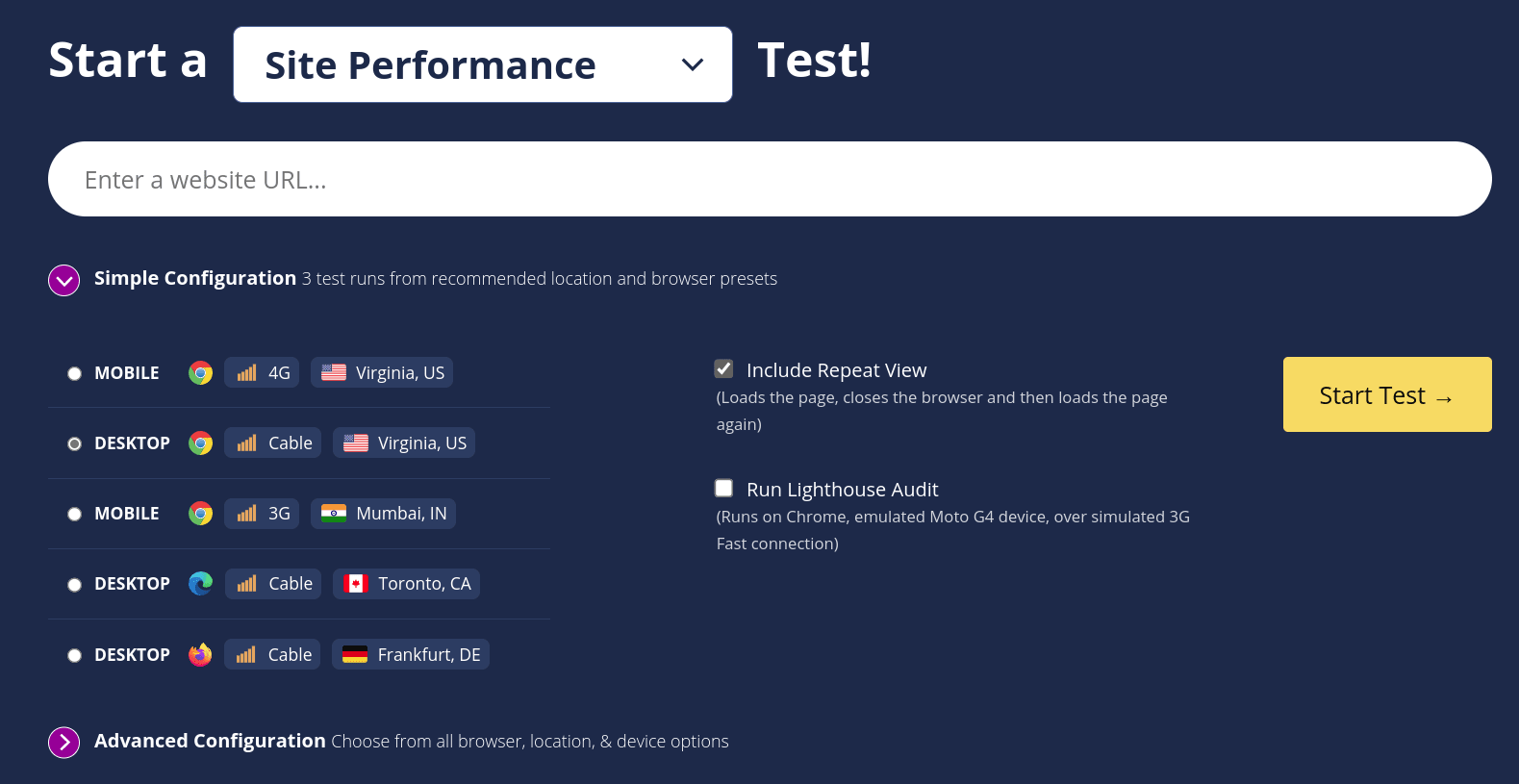

If you’re running analytics on a site, then you can use that data to work out the first/return visitor split for a given page. To figure out how much data return visitors download, you can run a page through WebPageTest & include repeat views.

The results page for the test will show you how much data was downloaded for the first view & how much was redownloaded for the repeat view. You can use this to work out a percentage of data that return visitors download, and plug that into the SWD model.

For CO2.js, we’ve got a couple of open issues asking to make adjusting these figures easier. It’s something that will be possible once v0.12 comes out. That will include new functions which allow users to pass in their own values for these variables. You can follow the pull request here.

Adjusting grid intensity

In the same pull request, we’re also planning to give users the ability to adjust the grid intensity used for different system segments. Let’s unpack some of that terminology for a second.

The way a carbon emissions estimation model works, is that it first calculates the energy used by an operation. It then multiplies this by a figure known as grid intensity. Grid intensity is a value that represents how many grams of CO2 is produce per kilowatt-hour of electricity generation on a given grid. This multiplication of energy usage by grid intensity gives us a carbon emissions estimate.

As I mentioned earlier, the SWD model uses a global average grid intensity figure for all its calculations. But let’s say that you know your server is in Germany and your users are in France. Then for those two parts of the emissions calculation, you’d ideally be using grid intensity figures specific to those locations.

Of the four system segments used in the SWD model - data centers, networks, devices, production - data centers and devices are the ones where location is most likely to be known and so can be adjusted for. Sometimes there could be a case where it is known network traffic is also limited to within one country, and so could also use a country-specific grid intensity figure. Given the nature of global supply chains these days, the global grid intensity figure is a good fit for the production segment.

There are a couple of ways to find grid intensity data. CO2.js include annual average grid intensity data for over 60 countries, or you can source this data from a provider like Ember. If you want to go all in and track emissions in real-time, then you’d need to use an API like Electricity Maps or WattTime.

Per request weight, rather than page weight

Okay, this one’s a bit hardcore, but if you’re using a model like SWD to work out the emissions of an entire page, then it’s definitely worth considering.

From my experience with website carbon calculators, most seem to take the entire page weight & put that through the SWD calculation to return a CO2 estimate. That’s well and good, but if you’re using a testing tool like Google Lighthouse to get the page weight, then you’ll also have access to data about every request made when that page loads. You can see where I’m taking this, yeah?

If we calculate the emissions of each request individually, and then tally them together, we have the potential to get to an even more accurate estimate. This is especially the case when coupling this approach with the adjustments talked about above. There are varying degrees to how far you can take this, each returning more accurate results. I talk through them below and each one builds on the ones before it.

- Calculate the emissions of each request using the regular SWD model. This will return a result that’s probably going to be within a rounding error of the result you would get from using the total page weight.

- Check each request for green hosting, and use the renewables grid intensity for the data center segment of that request. In this scenario, if you have even one green hosted request you should get a number that’s lower than if you were to just use total page weight.

- You can check for green hosting using the Greencheck API.

- The SWD model uses a renewables grid intensity of 50 g/kWh.

- Check the location of each request’s host, and use the grid intensity for that location in the data center segment calculations. Results here could be higher or lower than if you just used total page weight. If you have a lot of requests served from regions that have high grid intensity, then this will skew the result up. Likewise, if you have more requests coming from lower grid intensity regions, you’ll get a lower emissions estimate.

- If you know a requests host IP address, then you can check its location using the IP to CO2 Intensity API. This API also returns the annual average grid intensity for locations.

- What we’ve done above is just for the data center segment. If you know the location of the device viewing the site, then you could also plug in those figures.

- Check if the result is not cached, and adjust the data downloaded by returning visitors figure accordingly. A request might have

max-age=0orno-cacheset incache-controlheaders. These requests will be downloaded each time any visitor loads the page. You could adjust the SWD calculation to reflect this. It will result in a higher emissions estimate.

Swap in known emissions values

Finally, there might be times when you actually know the emissions associated with one segment of your website. Perhaps your hosting provider is able to give you an annual breakdown of the emissions associated with hosting your site. In that case, you could calculate annual emissions for all other segments, and then add in the known emissions you have.

Or, perhaps you know the energy associated with loading a page on device (see: CO2e estimates in Firefox Profile). Here, you could calculate the emissions of other segments for a page view, and then add in the device emissions you know.

Rounding off

Measuring, and reporting on, carbon emissions is going to become an ever more important part of doing business. That said, it’s not practical to expect web developers or IT teams to drop everything and acquire the complete domain knowledge to build out carbon emissions estimation tooling.

Frameworks for calculating estimates, like the Sustainable Web Design model, are important tools in helping people get started down this path. As we’ve covered in this post, they can help you get an initial ballpark estimate. With a few tweaks they can be refined to produce results that are far more accurate and representative for a given website.